Disruptive change and the growing need for e-learning innovation

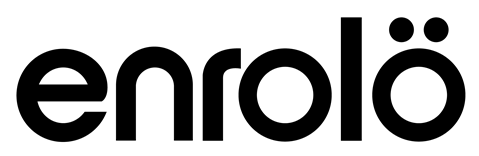

Today’s corporate leaders recognise that the pace of technological change is creating a major skills problem for their organizations. In a recent study, Deloitte found that 90% of CEOs believe their company is facing disruptive change driven by digital technologies, and 70 percent say their organization does not have the skills to adapt (Deloitte 2017: 30). Indicating some of the factors driving this problem, Deloitte point to the changing nature of a career, as follows.

The changing nature of a career (Deloitte 2017:30)

Clearly, with such frequent job changes and rapid skill obsolescence, there’s a significant demand placed on continuous learning and skills development. Thus, in many ways, individual and organizational performance now critically depends on the capability of e-learning providers to meet these demands. But how can e-learning leaders and innovators respond to this problem?

It’s useful to first get a little historical perspective.

Learning & Technological Change

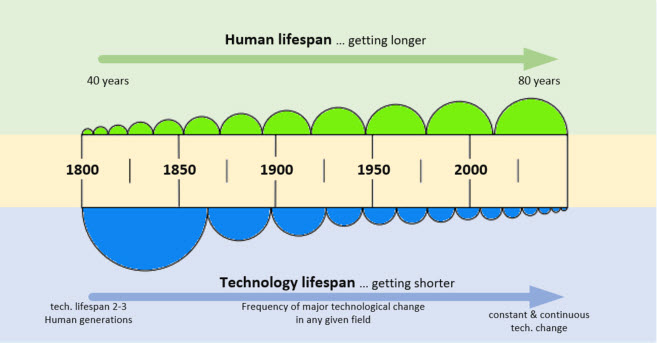

The skills challenges outlined by Deloitte are the modern outcome of a long-term trend.

In earlier times, widely-used technologies and skills would remain mostly unchanged for generations. People could learn everything they needed from their parents and grandparents. Broader knowledge was sparse and slow-changing. For example, in Europe, Burke (1985) explains that Martianus Capella’s (5th century) book on the seven liberal arts became “all the education there was for the next 700 years”.

In later times, as knowledge and technologies started to change, schools and universities provided intensive bursts of education – ideally enough to last a lifetime. However, the pace of change has increased, leading to the situation described by Deloitte. For an overall perspective, the long-term trend can be understood by looking at the relationship between human lifespans and technology lifespans, as shown below.

Human lifespan vs technology lifespan (adapted from Scholte 1988:31)

In modern times, things just move too quickly for many of our traditional approaches to education. Intensive bursts of formal education can no longer last a lifetime. Job descriptions change and blur. Key knowledge and skills become obsolete as entire industries fade and others emerge.

In these circumstances, there is a growing number of reasons why traditional education can’t keep up. And even faster-paced e-learning needs solid innovation and transformation.

The following sections explore ways that e-learning might respond to these challenges.

Rapid change & e-learning content development

It takes time to develop quality learning content – to make sense of a domain of activity, to distil the relevant insights, and to design content that helps establish these in the mind and practices of a learner. It can be time-consuming and costly. Given the rate of technological and skills change above, the challenges of content development are likely to increase. Deloitte (2017) points out one pathway forward:

“The good news is that an explosion of high-quality, free or low-cost content offers organizations and employees ready access to continuous learning. Thanks to tools such as YouTube and innovators such as Khan Academy, Udacity, Udemy, Coursera, NovoEd, edX, and others, a new skill is often only a mouse click away.”

This suggests a pathway involving something more along the line of e-learning content curation, drawing upon the best of what already exists and is freely available. Another related strategy might be to parallel the concept of “mashups”, creatively mixing this free content to support a specific learning need and context.

Such approaches will prove vital – but they will not be enough. This is because, historically, learning content authors have been able to draw insights from already-established and widely-accepted bodies of (mostly published) knowledge that may have been developed over generations. However this approach is under threat because it takes time for these bodies of knowledge to form; indeed, in times of rapid technological change, they may not get to even approach this point before another technological disruption occurs. This suggests a future where learning shifts to the workplace front-line, actively supporting knowledge development and application in everyday activities.

Micro-learning and micro-credentials

Another response to the pace of change is to focus on a smaller and ongoing stream of workplace and on-demand learning activity – in essence, learning all the time, and using micro-learning and micro-credentials. Eades (2014) explains micro-learning as “delivering content in small, very specific bursts”; and on this same theme, micro-credentials involve providing formal recognition for skills and knowledge gained from on-the-job experience which can be “stacked” to form recognised qualifications (O’Keefe 2016). Practically, some of the main challenges of micro-learning will center upon:

- Identifying the workplace time and context for e-learning – for example, should it be when a person has struck a problem they need learning to address, or perhaps artificial intelligence could be used to anticipate what additional learning a person might need, such as before a scheduled client meeting. (For more on this, consider Friedman’s discussion of “Intelligent Assistants”, in Takahashi 2016).

- Ensuring that learning content is concise and relevant enough to leverage the learner’s current situation – for example, a long-winded explanation of marketing theory is likely to distract from the task-at-hand, and in contrast, perhaps, an analytical tool that helps a person address their immediate task or challenge. A key here seems to be leveraging the learner’s current situation, and their mental focus upon it, as the framing context for a learning activity.

- Ensuring cognitive continuity between workplace task and learning – for example, having to go to a specific training room is likely to be problematic, and in contrast, consider the value of mobile-based learning content that can be accessed immediately and within the current workplace context.

Tracking micro-learning

A challenge for the micro-learning approach is keeping track of an individual’s learning activities. One approach was explored in the Institute for the Future’s “Learning is Earning 2026” project. This project considered a very broad approach to learning and learning providers, with some interesting possibilities (see the project video, below) – and a central part of this they called “the Ledger”. They explain:

“In this future, the currency of learning is tracked and traded on a digital platform called the Ledger. It’s a complete record of everything you’ve ever learned, everyone you’ve learned from, and everyone who’s learned from you. The Ledger not only tracks what you know – it also tracks all of the projects, jobs, gigs, and challenges you’ve used that knowledge to complete.” (http://www.learningisearning2026.org/)

The foundation envisaged for the ledger concept is blockchain – the technology that underpins crypto-currencies like Bitcoin. There are various explanations of its potential for learning, but the essence is that it provides a way to keep an accurate and trusted records of historical activity – in the learning context, records of the activities a learner has completed.

The reality is that this technology faces some hurdles to being applied in a learning context. For example, the Bitcoin blockchain handles relatively simple and well-defined information: it deals with currency transactions. In contrast, a learning-focussed application of blockchain may need to record information about a learner, the person or authority certifying the learning, the deliverer of the learning, the content and version of the learning, and potentially submitted work and assessment information. Meanwhile, Flipo and Berne (2017) point out that the computer facilities that underpin the Bitcoin blockchain already consume electricity on a scale equivalent to the country of Ireland, and that even widespread adoption of Bitcoin would have grave energy consequences globally. A blockchain of complex learning data would, in all likelihood, quickly surpass Bitcoin’s energy impact.

Beyond these issues, the need and potential for strategies that address accelerated skills and learning needs remains. There will be ways forward. And while some details are yet to be established, the scenarios contemplated in the Institute for the Future’s project provide some interesting glimpses into ways that micro-learning, rapid skill development, and ubiquitous workplace and lifelong learning might play a role.

[Youtube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcP78cLPGtE ]Paul Wilson elearning Consultant

References

Burke J (1985), The Day the Universe Changed, BBC, London.

Deloitte University Press (2017), “Rewriting the rules for the digital age”, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/HumanCapital/hc-2017-global-human-capital-trends-gx.pdf

Eades J (2014), “Why Microlearning is huge and how to be a part of it”, eLearningIndustry.com, accessed at: https://elearningindustry.com/why-microlearning-is-huge

O’Keefe D (September 21, 2016), “Old ways not enough to gain workplace credentials”, The Australian, accessed at: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/old-ways-not-enough-to-gain-workplace-credentials/news-story/286a526a99fc866f96f99cdac2c6981a

Flipo F & Berne M (2017), “The bitcoin and blockchain: energy hogs”, The Conversation, accessed at: https://theconversation.com/the-bitcoin-and-blockchain-energy-hogs-77761

Learning is Earning 2026: http://www.learningisearning2026.org/

Scholtes PR (1988), The leader’s handbook: a guide to inspiring people and managing the daily workflow, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Takahashi D (December 7, 2016), “New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman tells us how to live in accelerated times”, Venture Beat, accessed at: https://venturebeat.com/2016/12/07/new-york-times-columnist-thomas-friedman-tells-us-how-to-live-in-accelerated-times/